Introduction to Economics for SHS students: Definitions, Concepts, and Career Insights

Imagine this: You have GH¢50 to last you a whole month for snacks, data, and other personal needs. However, you have a wish list of things that costs far more than GH¢50. You’ll quickly realize you can’t buy everything you want – you must choose what to get now and what to leave for later. This simple scenario is economics in action. Economics helps us understand how to make choices when resources (like money, time, or materials) are limited but our wants are unlimited.

Welcome to this Introduction to Economics for SHS students (and any beginner across the globe). In this comprehensive guide, we’ll break down the definition of economics, explain basic concepts (like scarcity, opportunity cost, etc.), outline the branches of economics, describe different economic systems, introduce the tools of economic analysis, and even explore career paths in economics. By the end, you should have a solid foundation in “What is Economics?” and how it applies to your life and future. Let’s dive in!

{getToc} $title={Table of Contents} $count={Boolean} $expanded={Boolean}

What is Economics? Definition and Meaning

At its core, economics is the study of how individuals, businesses, and governments use limited resources to satisfy unlimited wants and needs. In other words, it’s about choices and trade-offs. Every day, people and societies decide how to spend their money, time, and effort – and economics examines those decisions and their consequences.

To better understand what economics means, let’s look at some famous definitions of economics from leading economists:

Adam Smith’s Definition of Economics (Wealth Definition)

Adam Smith – often called the father of economics – provided one of the earliest definitions of economics. He focused on wealth creation. According to Adam Smith, “Economics is the science of wealth.”byjus.com This means economics was seen as the study of how nations produce and acquire wealth. In his landmark 1776 book The Wealth of Nations, Smith examined how individuals pursuing their own gain can lead to wealth for society as a whole. Smith’s view was that by understanding production, distribution, and exchange of goods (i.e. wealth), we can figure out how to make a nation prosperous.

In simple terms: Adam Smith’s definition centered on money and goods – how people produce wealth and use it. While this was a good start, it was somewhat narrow (focusing mostly on material wealth).

Alfred Marshall’s Definition of Economics (Welfare Definition)

Economists later felt Smith’s definition was too narrow because it ignored human wellbeing. In 1890, Alfred Marshall expanded the definition. Marshall said economics is “the study of man in the ordinary business of life.”byjus.com In his view, economics is not just about wealth, but about people and their welfare.

Marshall’s definition means economics examines how people earn income and use it to achieve well-being. It’s a study of both wealth and welfare. He famously stated that economics is on the one side a study of wealth and on the other (more important) side a study of well-beingbyjus.com.

In simple terms: Alfred Marshall shifted focus to everyday life and people’s welfare. Economics, to him, was about how people make a living and how that affects their quality of life.

Lionel Robbins’ Definition of Economics (Scarcity Definition)

In 1932, Lionel Robbins introduced a definition that has become very influential. Robbins defined economics as “the science which studies human behaviour as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses.”pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. This sounds complex, but let’s break it down:

- “Ends” are wants or goals (the things we desire). Our ends are virtually unlimited – we always have more wants (for goods, services, better living conditions, etc.).

- “Scarce means” are limited resources (like money, time, raw materials) that we use to achieve those ends. “Scarce” means there isn’t enough to satisfy all our wants.

- “Alternative uses” means those limited resources could be used for different things. For example, you can use a piece of land to build a school or a market – you must choose one use over others.

Robbins’ key idea is scarcity. Because resources are scarce and can be used in many ways, we must make choices. Every choice has a cost (if you use your resource one way, you give up other alternatives). This definition highlights opportunity cost (more on that soon) as central to economics.

In simple terms: Lionel Robbins said economics is about scarcity and choice. We have limited resources but unlimited wants, so we constantly face trade-offs. Economics studies how we make those choices and allocate resources efficiently.

Modern Understanding of Economics

Combining these perspectives, we can say today: Economics is the social science that studies how individuals, businesses, and societies choose to use limited resources to satisfy unlimited wants, and how those choices impact well-beingsnhu.edusnhu.edu. It’s both about wealth (resources, money, goods) and welfare (people’s well-being), and it fundamentally revolves around scarcity and choices.

In everyday language, economics is about making choices when you can’t have everything. It’s as relevant to a student managing pocket money as it is to the Government of Ghana deciding on the national budget.

Now that we know what economics is, let’s explore some basic concepts of economics that stem from this definition.

Related post: {getCard} $type={post} $title={SHS Economics}

Basic Economics Concepts for Beginners

Economics has a few fundamental concepts that form the foundation of all further study. As an SHS student, understanding these will help you grasp more complex ideas later. The basic economics concepts include scarcity, choice, opportunity cost, scale of preference, and the basic economic problems every society faces. Let’s go through each in a simple way.

Scarcity – Unlimited Wants vs. Limited Resources

Scarcity is the central problem of economics. It refers to the basic fact that our wants are unlimited, but the resources to satisfy those wants are limitedbyjus.com. Think of resources as anything that helps produce goods or services we use: money, time, land, water, labor, tools, etc. No matter how rich a person or country is, resources are never infinite. There’s always a limit – which means we cannot satisfy every want.

In Ghana and other countries, for example, there’s a limited amount of money in the budget, but many projects (schools, hospitals, roads, etc.) that people desire. You as a student have limited time and money, but many things you’d like to do or buy. This mismatch between wants and resources is scarcity.

Factors of Production: Economists categorize resources into four main groups, often called the factors of production: Land, Labour, Capital, and Entrepreneurship.

- Land refers to natural resources (land itself, minerals, forests, etc.).

- Labour is human effort and time used in production (workers, your study time, etc.).

- Capital means man-made resources used to produce other things (machines, tools, buildings, money capital).

- Entrepreneurship is the organizational and risk-taking ability to bring the other factors together to produce goods or services.

All these resources are scarce – there’s only so much fertile land, a limited number of working hours in a day, a limited amount of money or machines, etc. Because of scarcity, we have to prioritize how to use resources best.

Choice and Opportunity Cost

Scarcity forces choice. If you can’t have everything, you must choose what is most important. Every day, individuals and society make choices about what to do with their limited resources.

However, whenever you choose one thing, you are giving up something else – that something you give up is called the opportunity cost. Formally, opportunity cost is the next best alternative forgone when a decision is mademytutor.co.uk. It represents the real cost of your choice – not in Ghana cedis, but in terms of what you sacrificed.

For example:

- If you spend two hours after school studying Economics, you give up the opportunity to use those two hours for something else (like playing football or watching TV). If playing football was your next best option, that is the opportunity cost of studying.

- If the government decides to build a new highway, the opportunity cost might be not building a number of schools with that money. The next best alternative (schools) was forgone to build the road.

Opportunity cost helps us weigh our decisions. Rational decision-makers (which economics assumes people try to be) will choose the option which they value more, understanding they must give up something else. It reminds us that “there’s no free lunch” – even if something seems free, there’s always an alternative use of resources that is being given up.

Scale of Preference

When faced with scarcity and choices, how do we decide what to choose first? This is where the concept of a scale of preference comes in. A scale of preference is simply a list of wants or needs ranked in order of importance or priorityyen.com.gh. We arrange our wants from the most urgent/important to the least important.

- For an individual, your scale of preference might put essential needs at the top (for example, lunch or transport fare might rank above buying a new video game, because food and getting home are more urgent).

- For a country like Ghana, a scale of preference might rank critical infrastructure and healthcare above less urgent expenditures, especially when funds are limited.

By listing out and ranking wants, decision-makers can allocate resources to the most important uses first. The scale of preference thus guides choice – you satisfy the highest priority want that you can, given your limited resources, and postpone or sacrifice the lower priority ones.

The Basic Economic Questions (What, How, For Whom)

Scarcity also means every society (or individual, or business) must answer some fundamental questions about resource use, often known as the basic economic problems:

- What to produce? – Given limited resources, which goods and services should be produced, and in what quantities? (For a country: how much of resources should go into education, defense, agriculture, etc.? For a student: what subjects or skills should you spend your study time on?)

- How to produce? – What methods will we use and how will resources be combined? (Labor-intensive or capital-intensive? Use local raw materials or imported ones? For example, should electricity be generated by building more dams or by solar farms? Which is more efficient given resources?)

- For whom to produce? – Who gets the output or benefits? (How are goods and services distributed among people? Does everyone get an equal share, or based on who can pay, or some other system? For a government, this might involve policies to decide which groups benefit from public spending.)

Every economy (from a small village to the whole country) has to answer these questions because of scarcity. Different economic systems (which we’ll discuss later) answer them in different ways. But no one can escape making these choices – not even you in your daily life. For instance, if you have a laptop (resource) and both your sibling and you need it (want), you must decide what to use it for (homework or entertainment?), how to share it (maybe take turns, that’s the method), and who gets priority (perhaps homework use gets priority over games – answering for whom first).

Understanding these basic problems will help you appreciate why economies are organized the way they are and why policy choices can be difficult.

Practical Example (Putting It All Together)

Let’s put scarcity, choice, opportunity cost, and scale of preference together in a student context:

- You have a Saturday with the following wants: do homework, play football, help your parents at the shop, and rest. Unfortunately, you cannot do all of these fully because the day has limited hours (scarcity of time).

- You list these activities by importance: maybe (1) help parents (important family duty), (2) homework (to keep up at school), (3) rest (you’re tired), (4) football (for fun). This ranking is your scale of preference.

- Based on this, you decide to spend the morning at the shop helping your parents and the afternoon doing homework. By evening, you’re out of time and too tired, so you skip football. You chose the top priorities.

- The opportunity cost of helping your parents and doing homework is missing out on the football game (your next best alternative) and some rest time. You gave those up for something more important.

- By making this choice, you essentially answered: What to do with your Saturday (help at shop and study), How to do it (maybe multitask a bit or schedule tightly), and For whom (you split time between family business and your own education).

This scenario might seem simple, but it’s truly economics at play in everyday life!

Now that we’ve covered individual-level basics, let’s see the bigger picture in the branches of economics.

Branches of Economics

Economics is often divided into two main branches: Microeconomics and Macroeconomics. Understanding the difference between them is important as you advance in economics studies. Both branches deal with economic issues, but on different scales.

Microeconomics

Microeconomics is the branch of economics that studies individual units – it looks at how individuals, households, and firms make decisions and how they interact in specific marketsm.economictimes.com. The prefix “micro-” means small, so microeconomics zooms in on the small parts of the economy.

Key things microeconomics examines include:

- Consumers and households: How you decide what to buy given your income, how families budget their expenses, what influences your decision to purchase item A instead of B.

- Firms and businesses: How a firm decides how many goods to produce, what price to charge, how to minimize cost and maximize profit.

- Markets for goods and services: How supply and demand interact to determine prices and quantities. For example, how does the market for rice in Ghana work? If there’s a bad harvest (less supply), what happens to price? Micro looks at such specifics.

- Individual markets for resources: e.g., the labor market – how wages are determined for a specific job, or how many people a company will hire.

A simple microeconomic example: how the price of bread is determined in Accra. Bakers (suppliers) decide how much bread to bake based on costs and the price they expect, consumers decide how much bread to buy based on their need and the price. The interplay of these decisions (supply and demand) in the bread market will determine the price of bread. Microeconomics provides tools (like demand and supply analysis) to study this process.

In summary, microeconomics = the study of individual economic units and specific markets. It answers questions like “How will an increase in petrol prices affect the cost of transport for a family?” or “How does a new tax on mobile phones affect the phone market?”

Macroeconomics

Macroeconomics, on the other hand, is the branch that studies the economy as a wholeaier.org. The prefix “macro-” means large, so macroeconomics looks at the big picture – aggregate outcomes and broad trends, rather than individual choices.

Key topics in macroeconomics include:

- National output (Gross Domestic Product, GDP): How much is the entire Ghanaian economy producing in goods and services? Is the economy growing (GDP increasing) or shrinking?

- Overall price level and inflation: Are prices in general rising (inflation)? What is Ghana’s inflation rate and what causes it to go up or down? How can it be controlled?

- Unemployment: What percentage of the labor force is unemployed? What policies can create jobs?

- Government budgets and spending: How government taxation and expenditure influence the economy (fiscal policy).

- Money, banking, and interest rates: How the Bank of Ghana manages money supply and interest rates to stabilize the economy (monetary policy).

- International trade and finance: Ghana’s exports (like cocoa, gold) and imports, exchange rates of the Ghanaian Cedi, and how global economic trends affect the local economy.

A macroeconomic example: inflation in Ghana. If macroeconomists observe that inflation is, say, 10% (prices on average 10% higher than last year), they analyze broad causes – maybe excessive money supply, higher import costs, etc. They’ll look at economy-wide policies to reduce inflation, such as adjusting interest rates or government spending. This is not about one market, but about all markets together.

In summary, macroeconomics = the study of the whole economy. It answers questions like “Why is the cost of living rising in the country?”, “What can the government do to reduce unemployment?”, or “How can a nation achieve sustained economic growth?”

Micro vs. Macro in a Nutshell

To avoid confusion, remember:

- Micro = small scale (individuals and firms). Example: pricing of a single product, like what is the cost of a litre of milk and why?

- Macro = large scale (whole economy). Example: overall cost of living and why prices of goods in general are rising or falling.

Both micro and macro are important. They are like two lenses: one zooms in and one zooms out. Policies and events in the macro economy often affect micro decisions, and the sum of many micro decisions can shape macro outcomes. As an SHS student, you will study elements of both branches to get a balanced understanding of economics.

Types of Economic Statements: Positive vs. Normative

When discussing economics, it’s useful to distinguish between two types of statements or analysis: positive economics and normative economics. These terms refer to whether an economic statement is describing facts or value judgments.

- Positive Economics (Objective Statements): This deals with “what is”. A positive economic statement is objective, fact-based, and testabletutorchase.comtutorchase.com. It describes or predicts economic events without judgment. For example, “The unemployment rate in Ghana is 8%.” This is a positive statement because it can be tested against data to see if it’s true or false. Positive economics tries to explain or predict: If the government increases the VAT (Value Added Tax), what will happen to consumer spending? This can be studied by looking at trends and data – it’s not about whether it’s good or bad, just about cause and effect.

- Normative Economics (Subjective Statements): This deals with “what ought to be”. A normative statement is subjective, value-based, and includes opinions or judgmentstutorchase.com. It reflects what someone thinks is good or bad, or what policies should be adopted. For example, “The government should provide unemployment benefits for all jobless persons.” This is normative – it’s about what ought to happen, based on values or ideals. Normative economics often appears in policy debates: Should taxes be higher on the rich? Should the minimum wage be increased? These involve opinions and cannot be conclusively proven right or wrong by facts alone, because they depend on societal values.

Examples to differentiate:

- Positive: “When the price of petrol goes up, the cost of transportation increases, and people tend to travel less.” – This is a factual cause-effect statement (and indeed, historically we can observe that higher petrol prices lead to less petrol purchased). It’s something that can be checked with data or economic models.

- Normative: “Petrol prices are too high, the government should reduce fuel taxes to make life affordable.” – This is an opinion on what policy should be (maybe a widely held opinion, but still a value-based statement). Words like “too high” or “should” are clues to normative statements.

As a student, it’s important to recognize the difference. Positive economics helps us understand and predict, using analysis and evidence. Normative economics injects our goals and values – what do we want the economy to be like? Both are useful: we need facts to understand the world, and we need values to guide decisions. Just be clear which is which.

In exams or discussions, if a question asks for positive analysis, stick to facts and logic. If it asks for normative views, you can discuss what should be done (and even then, back it up with positive analysis!).

Now, how do economists actually go about studying these questions and statements? They use certain tools and methods. Let’s look at the tools of economic analysis next.

Tools of Economic Analysis

Economics is not just theories and concepts – it also uses practical tools to analyze data and trends. Think of these as the “equipment” economists use to understand the economic world. Here are some fundamental tools of economic analysis:

- Tables and Charts: Economists often organize data into tables (rows and columns of numbers) to see patterns, or use charts to present information visually. For example, a table might show Ghana’s GDP for each year from 2010 to 2020. A chart can convert that into a visual graph, making it easier to see trends (like GDP rising or falling). Charts could be bar graphs, line graphs, pie charts, etc., each useful for different kinds of data.

- Graphs (Diagrams): Graphs are extremely important in economics. They plot the relationship between two or more variables. For instance, the demand and supply graph is a basic tool: price on one axis, quantity on the other, showing how they relate. Graphs help in analysis by showing trends or intersections (like equilibrium where demand meets supply). You’ll encounter graphs like the Production Possibility Curve (PPC) which illustrates opportunity cost, or curves that show how changes in one factor affect another. Being comfortable reading and drawing graphs is crucial for economic analysis.

- Mathematical Models and Equations: Modern economics often uses mathematics to formulate theories precisely. An economic model might be a set of equations or formulas that represent how the economy or a part of it works. For example, a simple equation might express consumption as a function of income. Equations allow economists to calculate important values (like elasticity, which measures responsiveness to price changes) and to make predictions. Don’t worry, at SHS level the math is usually not very advanced – basic algebra and arithmetic is often enough to grasp the models you’ll see.

- Statistics and Data Analysis: Since economics uses real-world data (prices, quantities sold, incomes, etc.), statistical tools are used to analyze this data. Statistics help summarize data (e.g., finding average income, inflation rate) and test relationships (e.g., does higher education level correlate with higher income?). Economists might use statistical methods to verify if evidence supports a theory – for example, checking if data shows that “when price rises, quantity demanded falls” (Law of Demand) generally holds true. At an introductory level, you might not do complex statistics, but you should understand concepts like average (mean), percentages, growth rates, etc., since economic reports use them.

- Logical reasoning and diagrams: Aside from numbers, economists use logic and step-by-step reasoning (this can be called theoretical or conceptual tools). They construct arguments like: “if A happens, then B will likely follow, because…”. They also use flow charts or schematic diagrams to track processes (for example, the circular flow diagram shows how money and goods flow between households and firms in an economy).

- Computers and Software: In today’s world, economists also rely on computers to analyze big data sets and simulate models. While you won’t need to run software as an SHS student, it’s good to know that behind the scenes, things like spreadsheets (Excel), statistical software, and even AI tools are used to crunch numbers and forecast trends.

In summary, the basic tools of economic analysis include graphs and charts, mathematical models, and statistics (data analysis)brainly.com. With these, economists can take raw information and make sense of it, identifying patterns like “sales go up when price goes down” or forecasting what might happen if, say, the government increases spending.

As you proceed in economics, you’ll practice using some of these tools: drawing a demand curve, calculating an elasticity, reading a national budget table, etc. These skills help you to not just learn economics, but do economics – analyzing real problems systematically.

Economic Systems (Types of Economies)

Different countries or societies can organize their economies in different ways to answer the basic economic questions (what, how, for whom) we discussed. The way a society organizes economic activity is called its economic system. There are four main types of economic systems: traditional, command, market, and mixed economiessnhu.edusnhu.edu. Let’s look at each:

Traditional Economy

A traditional economy is the oldest type of system, found in societies that rely on customs, traditions, and beliefs to make economic decisions. Such economies typically center around survival and basic needssnhu.edu.

- Characteristics: In a traditional economy, people often follow their ancestors’ ways. If your grandparents were farmers or weavers, you likely will be too. Methods of production are traditional (not much modern technology). Trade might be done through barter (exchange of goods without money) in local communities.

- Examples: Some rural villages or tribal communities operate on traditional principles. For instance, in parts of Africa or Asia, a community might farm and hunt primarily to feed itself, trading any surplus with neighboring communities for other goods.

- Decision-making: The questions of what, how, and for whom are answered by tradition: they produce what they always have, in the way they always have, and distribute according to customs (for example, sharing within a family or community as per tradition).

Traditional economies are simple and community-driven. However, they often struggle to produce much surplus or grow significantly, and they can be vulnerable to changes (like drought or outside influence) because they don’t adapt quickly from established methods.

Command Economy (Planned Economy)

A command economy is one where the government makes all or most of the economic decisions. The government (or central authority) controls resources and production, rather than letting market forces decidesnhu.edu.

- Characteristics: In a pure command economy, the government decides what to produce, how to produce, and who gets the output. It might set production targets for factories, fix prices for goods, and determine people’s wages and jobs. Private property is often limited – resources are owned by the state.

- Examples: Historical examples include the former Soviet Union or North Korea. These governments controlled agriculture, industry, and distribution. Another example: during major wars, many countries temporarily use command principles (governments ration goods, direct factories to produce military supplies, etc.).

- Decision-making: The idea is that by planning everything, a command economy can mobilize resources quickly and achieve large projects (like building infrastructure or developing industry). However, without the signals from supply and demand, command economies often face shortages or surpluses because it’s hard for central planners to get the quantity “just right.” Innovation may also suffer if people and companies don’t have incentives to excel (since decisions and profits are controlled by the state).

In summary, command economy = government-controlled economy. A country like Cuba has elements of this (though most “command” economies today have incorporated some market elements, as pure planning proved inefficient).

Market Economy (Capitalism)

A market economy is one where economic decisions are driven by the free market – i.e., by buyers and sellers interacting with little government interventionsnhu.edu. This is often associated with capitalism.

- Characteristics: In a market economy, private individuals and businesses own resources (land, factories, etc.). They make production decisions based on market signals. Prices are determined by supply and demand – an idea famously explained by Adam Smith’s concept of the “invisible hand”, which suggests that individuals seeking their own gain in markets can lead to benefits for society as if guided by an invisible hand. There is free enterprise, meaning people can start businesses, choose their careers, and consumers can decide what to buy.

- Examples: The United States is a classic example of a largely market-based economy. Other countries like Australia or Singapore also lean strongly towards market principles. No economy is 100% pure market, but in these, markets have a dominant role in guiding decisions.

- Decision-making: The basic questions are answered through decentralized decisions:

- What to produce? Whatever consumers demand. If people want more smartphones and less DVD players, companies will notice sales and profit opportunities and shift to smartphones.

- How to produce? Businesses decide how to produce efficiently to beat competitors – maybe one firm uses more machines, another uses more labor, whichever is cost-effective.

- For whom to produce? For whoever is willing and able to pay – distribution is based on purchasing power in a free market. (This can raise issues of inequality, which is a known downside of pure markets.)

- Role of Government: In a pure market economy, government’s role is minimal – perhaps just to enforce contracts and property rights, and ensure no one cheats. In reality, most “market” economies still have some regulations and government programs (e.g., antitrust laws to prevent monopolies, safety standards, etc.), but they generally let markets run most of the show.

Mixed Economy

A mixed economy is, as the name suggests, a blend of market and command systems. Most countries in the world today, including Ghana, operate mixed economiessnhu.edu.

- Characteristics: In a mixed economy, some sectors might be left to the market, while others have significant government control or oversight. Both private enterprise and government intervention exist. For instance, private businesses operate freely in many markets, but government might regulate heavily or even own certain key industries (like electricity or water). Government also typically provides public services like education, roads, and security, which are funded by taxes rather than by the market directly.

- Examples: Ghana’s economy is mixed: it has many private businesses and market-determined prices, but the government also plays a big role in areas like utilities, education, and infrastructure. The United Kingdom or South Africa are also mixed economies – largely market-driven but with government welfare programs and regulations. The United States is mostly market-based but still a mixed economy because the government intervenes in areas like healthcare (partially), social security, etc. In fact, “most economies in the world are mixed economies”snhu.edu, as one economist notes.

- Decision-making: Mixed economies answer the basic questions through both market signals and government directives. Generally, everyday goods (like food, clothing, electronics) are produced and allocated by markets (what people buy and sell). Meanwhile, the government might decide on some larger issues: for example, subsidizing agricultural production of maize (thus influencing what to produce), or imposing environmental regulations on how to produce (to protect air quality), or taxing the rich to fund programs for the poor (affecting for whom goods and services ultimately go).

The goal of a mixed economy is to harness the efficiencies of markets while mitigating the downsides through government action. So it tries to achieve a balance: encourage enterprise and innovation, but provide social safety nets and ensure public needs are met.

For instance, Ghana operates as a mixed economy where you’ll see bustling open markets and private enterprises (market economy features), alongside government interventions like price controls on fuel at times, public education and health services, and state-owned enterprises in critical sectors (command economy features).

Which system is best? That’s a classic normative economics question. Pure command economies have largely fallen out of favor due to inefficiencies. Pure market economies can lead to inequality and market failures. So most agree some mix is necessary – the debate is just how much government versus how much market. For our purposes, know the definitions and traits of each system.

Now that you have a sense of how economies can be structured, let’s turn to something important for you as a student: if you pursue economics further, what careers can it lead to?

Careers in Economics

Studying economics can open the door to a wide range of career paths. It’s a versatile subject because economics training involves critical thinking, data analysis, understanding of how the world works, and decision-making skills. Here are some potential careers in economics that an SHS student might consider in the future:

- Economist (Policy Analyst): As an economist, you could work for government agencies (like the Ministry of Finance, Ghana Statistical Service, or Bank of Ghana), researching and analyzing economic trends to advise on policy. For example, governments employ economists to forecast economic growth, analyze the impact of policies (like how a new tax law might affect businesses), or manage national financial planning. Economists also work for international organizations (like the World Bank, IMF, African Development Bank) helping to design policies for development and advising multiple countries.

- Financial Analyst or Investment Analyst: Economics graduates often work in banks, investment firms, or insurance companies. As a financial analyst, you might evaluate investment opportunities, study financial markets, or analyze the economic health of companies. For instance, you could help a bank decide whether to loan money to a new business by analyzing the business plan and economic conditions, or you might work in the stock market analyzing how macroeconomic news (like interest rate changes) will affect stock prices.

- Economic Consultant / Researcher: Many businesses and non-profits hire economic consultants to analyze specific problems. As a consultant, you might study things like market demand for a new product, the economic impact of a project, or efficiency improvements for a company. Research institutions and think tanks (including those focused on economic and social research) also hire economists to conduct studies and publish reports on issues like poverty, education, and trade.

- Data Analyst / Statistician: Since economics teaches you to work with data, many economists work as data analysts. For example, you might join a tech company or an NGO in analyzing user data, market trends, or survey results to draw insights. In Ghana, organizations like the Ghana Statistical Service or research NGOs value economics graduates for their quantitative skills to analyze surveys (like the Population Census or Living Standards Surveys) and interpret the results.

- Academic (Teacher or Lecturer in Economics): With further studies (like a master’s or PhD), you could become a lecturer or professor of economics at a college or university, teaching the next generation and doing academic research. Even with a bachelor’s degree, you could teach economics at the high school level (for instance, becoming an SHS economics teacher) if you also get the necessary teacher training. Education is a rewarding career path where you can inspire students with economics knowledge.

- Business Management and Entrepreneurship: An economics background is useful if you start your own business or manage a company. You’ll understand market trends, pricing, and cost management better. Many CEOs and business leaders studied economics because it gave them a broad understanding of how industries and consumers behave. So while “entrepreneur” isn’t a job you apply for, economics can equip you with tools to run a successful enterprise (e.g., doing a cost-benefit analysis for a new venture, understanding your customer’s budget constraints, etc.).

- Other Specialized Roles: Economics can also lead to careers like Actuary (assessing risk for insurance, though that requires further training in statistics), Urban Planner (using economic analysis for city development plans), Policy advisor (for politicians or NGOs, crafting informed policies on health, education, etc.), and more. Even fields like law benefit from an economics background (there’s a field called Law and Economics).

One great thing about economics is its broad applicability. As noted by career experts, there are economics-related opportunities in virtually every sector – public sector, private sector, finance, international development, academia, and beyondsnhu.edusnhu.edu.

In Ghana, for example, you could find economics graduates:

- Working at Bank of Ghana as analysts monitoring inflation and banking sector health.

- Employed in commercial banks like GCB or Ecobank as financial analysts or investment officers.

- Joining NGOs or think tanks that focus on economic development, helping design programs to support small businesses or assess the impact of microfinance in rural areas.

- Serving in national service positions at ministries, using economic knowledge in departments like trade, agriculture, or energy to assist in policy formulation.

- Teaching in schools or writing for economic publications, explaining economic issues to the public (even writing blog posts like this!).

What kind of further education is needed? Generally, to call oneself an “economist” in a professional sense, one might go beyond SHS to get at least a Bachelor’s degree in Economics. Many higher-level economist roles (especially in research or government) prefer a Master’s degree or even Ph.D. in economics or a related field. However, many roles like financial analyst or business roles can be obtained with an undergrad degree, especially if you combine economics with other skills (like finance, accounting, or IT).

For now, as an SHS student, the key is that studying economics builds valuable skills – analytical thinking, data interpretation, understanding of how people and markets behave – which are prized in many careers. So even if you don’t become an “economist” by title, the knowledge can be a big asset in business, government, or any career where decision-making and analysis are important.

Conclusion and Further Reading

Economics may sometimes sound abstract, but at its heart, it’s a practical subject that affects everyday life – from the price of kenkey at the market, to the job opportunities available when you graduate, to the national policies that shape Ghana’s development. By understanding the definitions, basic concepts, branches, systems, and tools of economics, you’ve taken the first step in thinking like an economist. You’re now better equipped to understand news about the economy, make informed decisions in your personal life, and pursue more advanced economics studies or careers.

Keep exploring! Economics is a vast field, and this introduction is just the beginning. Feel free to dive deeper into any topic that caught your interest. For instance, you might want to learn more about how opportunity cost works in complex decisions or explore the laws of demand and supply which form the backbone of market economics.

For more on related topics, check out these other posts on our site:

- See our post on Understanding Opportunity Cost – for a deeper dive into opportunity cost with more examples.

- See our post on Demand and Supply Basics – to learn how prices are determined in a market and why they fluctuate.

By continuously learning and asking questions, you’ll soon develop a strong economic way of thinking that will serve you well in school and beyond. Happy learning!

Related post: {getCard} $type={post} $title={SHS Economics}

Review Questions

1. As a student, you are faced with how to spend your day

(6am to 12 noon) on

studying towards an examination that has been scheduled for

the next day,

attending a wedding ceremony of a friend, or going to the

stadium to watch a

football match.

a) Using the case study above, which of the activities would

you spend your

time on?

b) Give at least one reason for selecting that activity.

c) How does the case study relate to opportunity cost?

2. Group the following under positive and normative

Economics statement:

• The government ought to provide subsidies to farmers.

• An increase in population will put pressure on social

amenities.

• Cost of living will rise when there is an increase in the

general price levels.

• Rich people must be made to pay more taxes than the poor.

• High taxes reduce the profit levels of businesses.

3. Distinguish between microEconomics and macroEconomics.

4. Who is an Economist?

5. Identify at least two (2) career paths for the

professional Economist in private and

public agencies.

6. Identify two (2) ways Economists have contributed to the development of Ghana.

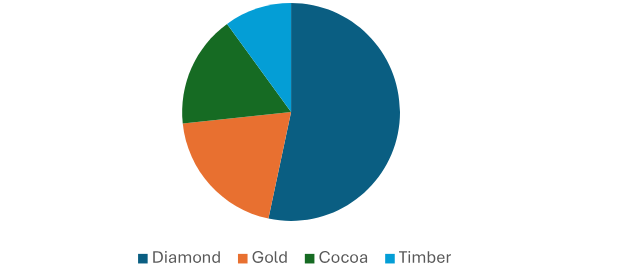

7. The table below shows the exports of cocoa from four (4)

West African countries

in the year 2018. Study it and answer the questions that

follow.

|

Exports of cocoa |

Quantity in metric tons |

|

Ghana |

800 |

|

Nigeria |

650 |

|

Cote d’Ivoire |

950 |

a. Calculate the total exports of cocoa in 2018.

b. Estimate the mean export of cocoa from West Africa in

2018.

c. Present the information from the above table on a pie

chart.

8. State two uses of graphs as tools of economic analysis.

9. In your own words, distinguish between needs and wants.

10. The table below shows how a student’s wants are arranged

according to his/

her priorities or importance. Use it to answer the questions that follow:

|

Items Prices |

Gh¢ |

|

Textbooks |

140 |

|

School uniform |

110 |

|

Provision |

130 |

|

Calculator |

180 |

|

Mosquito net |

70 |

|

School sandals |

50 |

|

Toilet roll |

30 |

a. What economic term is used to describe the table above?

b. If the student has an income of Gh¢1000.00 as his/her

only resource, which

of the following statement(s) will be true?

i. He/she has to forgo some of his important items.

ii. He/she will buy all his wants.

iii. He/she will make choice.

iv. He/she will be faced with the problem of scarcity.

v. Opportunity cost will be zero.

c. If the student’s income is Gh¢ 250.00.

i. What item(s) will he/she buy? Explain.

ii. What is the opportunity cost of buying the item(s) at

(c)? Explain.

d. If the student’s income reduces to Gh¢140.00,

i. What item(s) will he/she now buy? Explain.

ii. What is the real cost of buying the item(s) in (e)?

Explain.

11. In the Republic of Bankukrom, people are engaged in

various businesses. They employ others to work for them in order to make a

profit. Their government makes laws to regulate the activities of businesses

and also collects taxes from them.

i. Identify the type of economic system practiced in

Bankukrom.

ii. Give reason(s) for your answer in 11 (a) above.

iii. What are the possible motives of the owners of

businesses in Bankukrom?

iv. State at least one (1) advantage you will enjoy as a

buyer in Bankukrom.

Extended Reading

- https://youtu.be/LofY4SkKJtU

- https://youtu.be/TWR1JUO-C8w

- https://youtu.be/_qmGxgjzdiY?si=NyDImJ9Cdpkia8l2

- https://youtu.be/ETPuyZosfyQ?si=QFuMSQHQDo9aUQhm

- https://youtu.be/CjiW_tY0yJs?si=Fkn14PqzGBt5e-Pg

- https://youtu.be/08l3j5y3Qnc?si=c20JAwKz6lb8zAZe

- https://articles.outlier.org/economics-definition

- https://bscholarly.com/tools-for-economic-analysis/

References

- Baye, M.R. (2010). MicroEconomics and business strategy. McGraw-Hill Irwin, New York.

- Hubbard, G. R., Obrien, A. P. & Rafferty, M. (2013). MicroEconomics. Prentice Hall, New Jersey.

- Lipsey, R. & Chrystal, A. (2011). Economics. (12th Ed.) Oxford University Press Inc. New York.

- Mankiw G. N. & Taylor M. P. (2017) Economics. 4th Edition, South-Western Cengage, Ohio.

- Mankiw, G. (2014). Principles of MicroEconomics. (6th Ed.) Southwestern, Ohio.

- McConnell, C., Brue, S., & Flynn, S. (2011). MicroEconomics. (19th Ed.) McGraw-Hill, New York.